Family memento – Memories – Warsaw Uprising 1944 (Fragment of memoirs)

The creation of the

“Memory on the 60th anniversary of the Warsaw Uprising”

(Fragment of memories)

Two alarms

Our entire section, except for Andrzej Krupiński, showed up for the first emergency meeting on July 28, 1944 (Friday). I think there was some trouble with his notification. But I don’t remember the details. I do not remember who notified me, nor my farewells to my parents.

The meeting point was a small tenement house, probably two-story, at Podleśna Street, in the lower Marymont, near a fenced CIWF forest (now AWF). We were met by a few dozen crammed into small cellars. Some of them prepared incendiary bottles intended for fighting against tanks. They carefully poured the gasoline from the barrel into the jugs, and then into the “monopoly” bottles. These bottles were then carefully corked, sealed and covered with paper saturated with a substance which, when it came into contact with gasoline, caused it to ignite spontaneously, as it turned out later.

All this work was quite dangerous with the large number of people crowded, tense and nervous, twirling completely unnecessarily. In addition, after midnight, a Soviet raid began and, as usual, the bombs fell densely and completely accidentally. It was even hard to guess what they were aiming for. Two of them exploded unpleasantly close.

In the attic of the building there were observers who were to warn us about the visit of undesirable guests. Fortunately, they did not notice any movements of the German troops. In the morning we received orders to go home and remain on the alert. or many of us, this order has created a really difficult situation. At their place of residence, they were already “burned” and had nowhere to go back. Some recovered the “private” weapons stored especially for this occasion and had trouble hiding them again, and they were afraid – and rightly so – to hand over to the arms service. In view of the great shortage of weapons, the chance of recovering them at the next alarm was slim.

I returned home with Hanka Rychłowska, my fiancée. Our parents greeted us as if we were returning from a long and hard campaign. I was afraid to stay at home because – as our housekeeper Marynia used to say – “the whole tenement house knew that the doctor’s son had gone to the foresters”. Fortunately, the Germans did not have the head to deal with trifles such as catching single, exposed soldiers, and German confidants and overzealous “navy blue” policemen disappeared from the horizon and probably prepared an alibi for “after the war” or simply blew along with the Germans.

On Sunday, July 30 in the early afternoon, in beautiful, sunny weather, I went with Hanka to “take a walk around the city”. It was probably not the smartest idea. However, I was not able to stay at home.

trange, but I remember exactly the route of our walk. We left the house at Miodowa Street and walked along Krakowskie Przedmieście and Nowy Świat. The intersection of Jerozolimskie Avenue and Nowy Świat Street was surrounded by the army. I preferred not to check what was going on there. We turned into Chmielna and through Bracka we reached Plac Trzech Krzyży. Despite the beautiful weather, the streets were almost completely deserted. On the square, the exit of Aleje Ujazdowskie was crowded with barbed-wire trestles and sandbags. Behind them was an armored car, and then the “shacks” of the gendarmes. There was no point in pushing on. So we turned into Żurawia and through Krucza, Szpitalna, Napoleon Square, Świętokrzyska, Nowy Świat and Krakowskie Przedmieście, we returned home undisturbed by anyone.

Apparently, in the previous days, the Germans hurriedly evacuated from the “Bristol” hotel, throwing their belongings from the windows directly onto the trucks standing on the sidewalk. On July 30, nothing of the sort happened. The hotel was surrounded by barbed wire trestles, ground floor windows were partially covered with sandbags. There were reinforced checkpoints in front of the hotel, but there was no sign of panic or hasty evacuation.

We were home around five, maybe six-thirty. Until supper we sat in the dining room and talked to Mom, who was calmly cleaning up the cupboard cabinets. I don’t remember where the Father was. Perhaps he was taking a patient. Sometimes it happened on Sundays as well. Rather, I think he went downstairs to the pharmacy to chat with its owner, Master Dobrzański.

I suggested that Hanka stay with us for the night. After all, we expect an alarm at any moment. It can also be early in the morning and there will be trouble notifying you. We were warned not to notify by phone. Telephones can be turned off without notice, they are certainly tapped, and the sudden surge in the number of calls must arouse suspicion among the Germans.

his time my mother agreed without difficulty, although she did not like when Hanka stayed with us. She had nothing against her, but she believed that it was not fitting for a bride to stay at her fiancé’s house. I wanted to call Mrs. Rychłowska to inform her that Hanka will not be coming home for the night. But my mother took the receiver out of my hand, saying that it is better for her to have such a conversation.

Dinner was around seven, as usual. The father brought the latest and “solid” news from the front, the mood was good, the conversation was, as usual, about everyday events and troubles and, of course, about the situation at the front. I did not realize that this was my last dinner with Hanka, Mom and Sister and at my family home.

The conversation at the table continued long after dinner. Later, Hanka went to my room, which I always gave her when she stayed with us.

I don’t remember the next day and the next morning and morning. I don’t think anything special happened. It seems to me, but maybe it was a few days earlier that it was then that I persuaded my mother that it is worth buying non-perishable food just in case. Mum was against “hoarding” and making great supplies. This time she agreed, but probably mainly because I wanted to do something. I know that together with Hanka in Podwale and Piekarska Street I was buying some cereal, oil, onions, as well as candles and flashlight batteries.

We sat with Mum and Hanka at dinner. Father was in his office. Some unexpected patient tore him off the table. During the second course, Jurek Miller, the commander of our section, came literally like a bomb. He was in such a hurry because he still had a lot to do. He told us to come to the appointed assembly point as soon as possible.

I didn’t finish my dinner; I quickly changed into clothes prepared for the occasion: solid civilian trousers, a military training blouse with a set of insignia and an officer’s main belt (the same one I had in September 1939!). On the epaulettes of my shirt I had number 21, the pre-war infantry regiment to which our Military Training unit was subordinate.

I had bought solid new German military boots a few months earlier in Kercelak. My experience in the war so far has fully confirmed the opinion known to me that the most important part of a soldier’s uniform are shoes. All other items of clothing are substitutable or relatively easy to “organize”. It’s the hardest thing with shoes. And uncomfortable, undamaged shoes are – as our sergeant from PW used to say – worse than a jamming rifle. I only took out the nails, rightly reasoning that they should not make unnecessary noise.

I put a gray, worn-out summer coat over my PW shirt. On the shoulder, a bag with a change of underwear, a sweater, a towel, shaving accessories, a handy mini-first aid kit (prepared by the father), a canteen, a canteen and the so-called. toolbox (knife, fork and spoon in a common handle) – everything from PW equipment and a flat electric flashlight and a garden trestle, an excellent knife useful “for everything”.

Mom knocked on the doorstep and called Father. I remember him running out of the office in a flying apron. He was angry because no one dared to prevent him from seeing patients. He said goodbye to me a bit dryly – he didn’t like to show his feelings. On the other hand, he cordially said goodbye to Hanka, in relation to whom he had been clearly reserved so far, although he was always very polite towards her. I was aware that the Uprising would not be a game, although in the darkest assumptions I did not suspect its actual course. The father had a serious heart disease. I was counting on the fact that there was no great chance of experiencing the emotions of the Uprising.

Mom – she kept the governments in the house with a firm hand – was characterized by great mental resilience, which I admired many times during various dramatic occasions. This time she broke down and cried. She went to her dressing table and took out a medal and a “holy” picture and gave them to me. The picture, damaged by prolonged carrying in a wallet, but carefully framed, stands today in a place of honor in my house. She took out another of her rings with a beautiful large diamond, and she wanted me to take it. I refused; I remember exactly what I said: “I will always manage somehow, and it can still be very useful to you. You don’t know what awaits you. ”

My mother was crying, she urged me to take a better summer coat, the old one so worn. “Mom, he’s very bright, I’ll be too visible in him, better the old one.” Mom was still crying. I’ve never seen her like this before. I think she had a feeling that we would never see each other again.

My mother died with those who came to our house after a few days of the Uprising, my sister Danuta, her little son Jacek and Hanka’s mother – Maria Rychłowska – on August 26, when our house was bombed. At that time, my father treated the wounded man in the basement of the second annexe and thus survived. Our housekeeper was in a neighboring house in the basement where there was an artesian well; she went there to fetch water and also survived.

The farewell dragged on. I was afraid that I would also fall apart in a moment. To avoid this, I suddenly became a bit harsh and cynical. To this day, I cannot forgive myself for it. You had to take a light coat and leave it at least in the first quarter. Today I know that the ring was unfortunately no longer needed by anyone either. At the time, I felt that I had no right to take it from Mama. But it would certainly be easier for her if she knew that I had something of value from her that could also save me in some critical situation. Another thing, if I had worn it on my finger, I would have lost it in captivity anyway, as I had lost my watch, plucked from my hand by a KultTrager in an SS uniform.

My mother said goodbye to Hanka, but she was absent. This is how I saw her for the last time.

Podleśna Street

We got on with Hanka (Hanka Rychłowska died on August 2, 1944 – Boernerów) on a tram at the stop at the corner of Miodowa and Kapitulna. We reached Marymont without any problems, and then we reached Podleśna Street. The collection point was the same as a few days earlier. It contradicted the elementary principles of the conspiracy, but apparently it was no longer relevant. Our section assembled in the early afternoon. I did not understand why we were rushed together in such a hurry. Nothing happened at the assembly point. Colleagues from other teams kept coming until late in the evening, some after the curfew.

The night passed peacefully. The organization was more efficient than before. We were served hot tea, bread and soup. I do not know if it was an initiative of the inhabitants of this house or if our quartermaster services were already operational. You felt that the outbreak of the Uprising was a matter of the next few hours.

Our section is located not in the basement, but in a room, perhaps on the first floor, resembling a veranda. We were quite cold. I remember taking a sweater out of my bag. Hanka also changed. We were sitting on a bench covered with my coat. In the morning, we were given white and red armbands with a printed eagle, the letters WP (Polish Army) and platoon numbers (ours had the number 237) and ID cards of the Home Army. We got to know colleagues, commanders, we met friends who we knew belonged to the underground (or rather that it was impossible for them not to belong), but we did not know that they belonged to the same company or even a platoon.

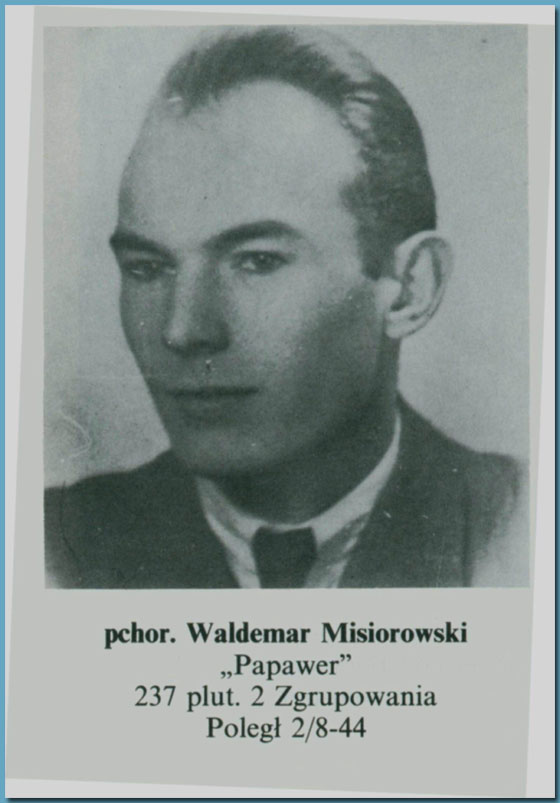

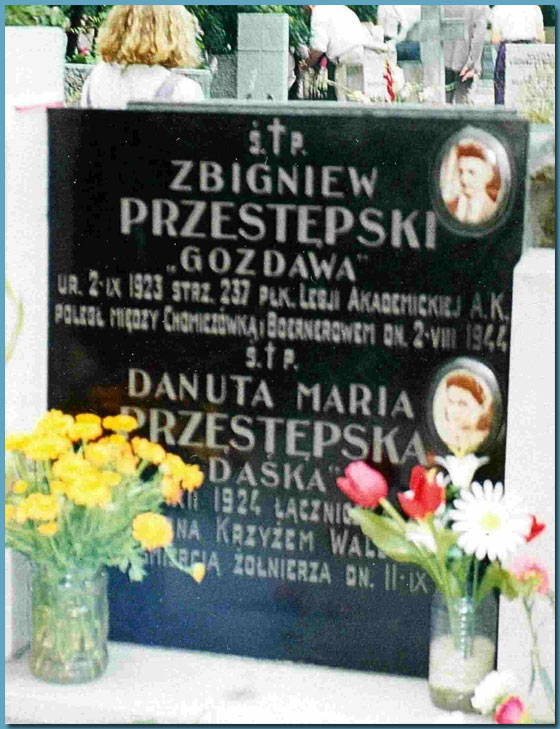

About one o’clock in the afternoon our platoon commander, Lieutenant “Dunin”, called me, Waldek Misiorowski (“Papawer”) and someone else from our section, probably Zbyszek Przestępski (“Gozdawa”). If it were Jurek Miller “ex officio” he would take the command, and moreover, his energy and outstanding individuality would have to make his participation remembered in my memory.

Dunin appointed me as the commander of this serious combat unit and gave us the order to reach Wilson Square to the gardening and hardware store (now there are delicatessen there) and report there with a note with “bland” content, which he had just given me to a gentleman with a nickname that I don’t remember today. We were to receive weapons there, which had to be delivered to Podleśna Street to our headquarters. We were supposed to go “civilian” and were strictly ordered not to get involved in any random action.

The three of us got on the tram. It was an old-fashioned open-platform car that was almost empty. There were only a few passengers. We stood on the front, empty, platform intended for “Nur fuer Deutsche”. At the second or third stop, a heavily flooded soldier in an air force uniform with anti-aircraft artillery badges boarded our platform. He had a little trouble staying upright, and in the holster there was an assault parabellum with a long barrel; our dream from the time of the occupation!

There was no doubt in the least that disarming a drunken hunk would not have caused us any difficulties. But the order we received was sacred to us, and regretfully it was necessary to give up the easy and much needed loot. Szkop must have sensed something, or maybe he could not stand our greedy glances, because all three of us were devouring his gun, because at the next stop he got out and looked uncertainly behind him.

We reached the store on Wilson Square without any problems. The store was literally cluttered with all sorts of shovels and rakes. pickaxes, chains, etc. A gentleman, whose pseudonym I don’t remember, we didn’t have to look for. He came up to us alone. He had no doubts who had come and what for. He was a well-built man with a southerly face and black, slightly grizzled hair. Later I saw him in Kampinos as a major of “Serb” (after he moved to Żolibórz, he changed his nickname to “Żubr”).

We received from him two Polish rifles in perfect condition, still greasy from the remains of grease, dismantled to facilitate their transport, and four pistols: one 7.65 caliber FN, two heavily damaged sixes and an “antediluvian” nine. On top of all this, some ammunition: a few magazines with cartridges for BB and a handful of pistol ammunition. As it turned out later, the latter was partially out of order.

FN “looked after” myself. I chose a dozen or so pieces of 7.65 caliber ammunition, loaded 7 into the magazine, and put the rest into my pocket. We carried the rifles dismantled, wrapped in gray paper. The other three pistols were put in the pockets of colleagues.

After leaving the store, before we even reached the tram stop, we heard the first, quite distant shots. As you know, the first fights in Żoliborz broke out prematurely. The gendarmerie stumbled upon scout troops carrying weapons by accident.

In this situation, we gave up using the tram. Anyway, he was not visible on the horizon. We turned off the street into allotments. We put on insurgent armbands, assembled and loaded the rifles and set off on foot towards Podleśna Street.

We got far and fortunately inaccurate rifle fire. Wandering through a completely unknown area, some allotment gardens, yards of poor Marymon’s houses, we moved “on the nose” towards Podleśna Street, getting hit by rifle fire over and over again. We were slowly losing hope that we would be able to join our colleagues.

The situation was getting worse. The sounds of shots came from all sides, but we did not see the insurgent troops anywhere. We heard series of machine guns, grenade blasts. Unexpectedly, we got under fire. We couldn’t figure out where they were shooting at us from. We got stuck to it, in a completely unfamiliar area, on some fences, walls, courtyards with no exit. Finally, when we did not know where we were, we saw “our” house in Podleśna Street around the corner of the street. Our colleagues were just coming out of it.

The company commander, lieutenant “Starża”, just in case, insulted us for being late, as if we were taking a walk for pleasure. However, we brought weapons, of which there were unbelievably few in the squad. Ours was literally worth its weight in gold. We handed it over to “Starży”. I completely “forgot” about my seven, although I was mercilessly crushed when I was stuck in the back of my trouser belt. Fortunately, no one asked for any documents relating to the weapons, no reports were requested.

The unit was jumping the street in small groups under fire from the CIWF and running towards Górny Marymont. If we had come literally 5 … 10 minutes later, there would be no trace of our ward and probably no one would be able to give us information where to look for it. Maybe it’s a pity that we were not late, maybe all my relatives would stay alive then: Hanka, colleagues and friends …

Before the Uprising, we were thoroughly acquainted with our first combat mission. We were to take over the area and buildings of the CIWF (the present AWF), in which the Germans were quartered and turned into a fortified area. The only theoretical chance of conquering this area was to act by surprise. There was no question of surprise anymore. The shooting in Żoliborz and Marymont lasted for at least two hours. In addition, the armament of our company was practically none: a few rifles, two or three submachine guns and maybe twenty pistols. There were only a lot of grenades. Usually the so-called “Sidolówki”, conspiratorial production. Reliable and effective as offensive grenades, but not very effective in defense. Attacking the fortified area without surprise, covering a large, partially forested area, could only be intended by some irresponsible fantasy with our forces.

Our company did not perform its task and thus we did not incur unnecessary losses. The remaining ones attacked the CIWF from the main entrance and guardhouse. The result was predictable: big losses and no success.

Attacks from various sides were to confuse the Germans and force them to divide their forces. They also made it more likely that one of them would succeed. The assumption was theoretically correct, but not with such a balance of forces, armament and no surprise.

We wandered the upper Marymont and Żoliborz streets, streets that were completely unknown to me, we jumped over some fences. This continued until the evening. None of us knew where and why we were going. Only one thing was clear: we did not even try to implement our basic task.

We had the first one before the evening. “Władek” (Władysław Brzozowski) from our section, stuck out from behind the wall behind which he hid, when we got into an unexpected, machine gun fire, literally the end of the elbow and the bullet shattered his elbow joint. It was a pure coincidence, because even a sharpshooter was not able to hit such a small target, the more so because we were fired from quite a distance.

I was next to Władek when he was injured and at first I did not understand what had happened. I thought he had hit his elbow on a wall and felt too much sorry for the painful but harmless event. However, the truth was quite different. The wound was not life-threatening, but very “malicious”, especially in the conditions of war. Despite careful care in the insurgent hospital (in the first days it was still possible), Władek was left with a stiff elbow forever. Perhaps the injury saved his life, as he did not take part in the Boernerow massacre.

Boerners

March out

In the evening, our company was located in the basement of the house, the location of which I am not able to even approximate. We were all very tired, hungry and completely surprised by how the situation unfolded. We didn’t even try to complete the task we were preparing for; we were tragically ill-armed, and the course of our journey and the expressions of our immediate superiors clearly indicated that our commanders did not know what to do. The mood was despicable, but anger at organizational inefficiency rather than doubts about the success of the Uprising prevailed.

Someone brought word that we were to go to Kampinos for gun drops. This message was denied in a moment. After some time, this topic began to be discussed again in the corners of our basement. Meanwhile, heavy rain began to fall outside. It was raining like hell. If we really are to make our way to Kampinos, now is the perfect opportunity: rain dampens steps well, visibility at night and in heavy rain is virtually nonexistent, and there is no point of fire. But nothing happened. Only our tiredness and nervousness with the situation increased.

Well after midnight, when most of us fell asleep somehow in the corners of the basement, an alarm was ordered and we went on an insured march, we were told, to Kampinos for weapons. The rain was still drizzling a bit, but after a dozen or so minutes it stopped raining completely. Someone maliciously stated that our command, out of concern for soldiers, was waiting for the weather to improve.

As I found out later, the entire battalion of captain “Serb” (later major “Żubr”) left Warsaw for Kampinos. Each of the battalion’s three companies followed a different path. Our second company, Lieutenant “Starży”, included platoons 212, 237 and 239. “Boy” team from the 237th platoon remained on the forward outpost in Bielany. Boy (Jan Ogulewicz) did not receive an order to join the platoon and was not informed about the company’s departure to the Forest.

I have not been able to establish whether it was a scandalous oversight or whether the liaison officer entrusted with this task did not arrive. However, I am convinced (on the basis of subsequent events) that it was neglect. The women liaison officers, who knew the area well, walked between Żoliborz and Bielany without much difficulty many days later. I also did not hear that the liaison officer sent by the company commander was lost or returned unable to get through. This kind of news spread instantly. We knew and valued our girls, we knew about the fate of each of them. The more we could not miss the information about the company commander’s liaison officer.

Boy’s team was not with us, but a number of people who did not make it to their units, as well as at least a few civilians, joined us. I don’t know how many of us went. There are very divergent opinions on this. There was a pre-war organization in the Home Army. The company had three platoons, a platoon – three teams, a team of 18 – 19 people, divided into three sections. The section was the smallest organizational unit in occupation, created for conspiratorial reasons. The section chief (theoretically) knew only five of his subordinates and the squad leader.

In practice, especially in the last period before the Uprising, when there was no time for reorganization, sections were often more numerous. For example, in my condition of 1 + 5 until the spring of 1944, “Władek” – a cousin of Staszek Witoszyński, who fled with his parents from the Eastern Borderlands from the Bolsheviks, and Hanka, who joined shortly before the Uprising, came. We received the consent of the superiors for such an extension of the composition of the section, but Hanka was to be transferred to a group of liaison officers or nurses. Of course, there were sections that were incomplete for various reasons, and certainly not all their soldiers reached. We were also accompanied by a group of civilians (perhaps candidates for soldiers who were to be incorporated into the Forest), who obtained the consent of the company commander. In my opinion, about 180 people were walking.

We were walking in an insured march. Szpica was led by 2nd Lt. “Zych” (Zdzisław Grunwald), followed by Lieutenant Starża (Jerzy Terczyński) with platoons 239 and 212. He was closing the marching column by Second Lieutenant Dunin (Jerzy Mieczyński) with platoon 237. A rear guard was also separated from this platoon.

We set off somewhere from the Marymont area, we jumped over Słowackiego Street more or less in the place where today the flyovers of the Armii Krajowej route are located. There was a German engineer park on the west side of the street. We walked about 200 to 250 meters from it. The Germans had to leave it, or they preferred not to risk the fight, as not a single shot was heard from their side.

Then we walked between the houses of the Workers’ Achievement (today’s Żeromskiego Street). There we stumbled upon two trucks loaded with cartons of German cigarettes. One of them was a bit shot, the other looked efficient. We tried to get it started, but our commanders advised us that we had no time to play and that we were not allowed to make any noise. So we stuffed our pockets and haversacks with cigarettes. The first catch, though accidental and we didn’t know to whom we owe it. Probably the cars were fired upon and their staff fled. At the same time, those who shot them could not get to them because of the fire from the German positions. After the night, both sides apparently preferred to stay quiet or withdrew.

Then we went through the so-called Swedish Mountains, that is the remnants of huge earth fortifications from the times of the Swedish wars. Today, there is not even a trace of them. They were located at the site of the later Bemowo airport, more or less at the level of Piaski or Chomiczówka.

We were in a great mood now. The prior despondency is over. finally we could see an organized action (we didn’t know anything about the lack of Boy’s team in our section); we were walking in an insured march to Kampinos for weapons. Conversations began among the marchers, sometimes too loud; someone laughed, someone stumbled and cursed loudly, someone’s canteen rattled.

This could not escape the attention of the commanders. Our section, which was also joined by a few colleagues from other sub-units, was approached by the platoon commander Dunin and sounded around us in an undertone. To separate this “discussion society” he stopped me and three unknown platoon colleagues. He told us to wait for the rear guard and loosen it.

The rear guard came almost as soon as the unit passed. They did not keep their recommended distance. Dunin rebuked them solidly for it. He told us to give us their two rifles, took them with him, and they ran to chase the column. He ordered us to follow her last soldiers at a distance of not less than 250 meters. We moved forward as the last colleagues from the column jumped over the cobbled road (which does not exist today) connecting Boernerowo with Wawrzyszewo.

Behind this road there was a large field, partially covered with freshly harvested grain. On the left side I recognized the Boernerowski grove. On the far right, I thought I recognized the outlines of an old Russian fort, one of those surrounding Warsaw on all sides. I knew the area fairly well. I have walked this way more than once during field military activities conducted in small groups. We pretended to be on a picnic trip. We came to Boernerowo by tram, with our girlfriends and typical picnic equipment and affectionate parks, we went to the forest. There, the boys gathered separately and started their classes, and the girls were trained and at the same time were our insurance. More than once it happened under the very nose of the Germans.

This time I was worried: after all, Jurek Miller had warned me a few days ago that a German armored unit was standing in Boernerów. But they had to get out, after all our intelligence works perfectly and the command needs to know what’s going on in the grass. They wouldn’t be pushing themselves in front of the Germans. Anyway, the head of the column must have passed, so my fears are unfounded.

Massacre of the 2nd company

When we got to the road that the last soldiers of the column had jumped a few minutes ago, we noticed that their march so far turned into a run. It was just starting to turn gray. There was some movement on the edge of the woods to the left. In a moment, one machine gun sounded from him, followed by a second and a third. Somewhere in the front, on the right, a small-caliber cannon (anti-tank?, Grenade launcher?) Sounded after a while. The squad was duplicated. Most of the boys had not been fired yet, had no or little combat experience. They fell behind and slowly crawled forward. The Germans have not noticed us yet. We jumped the road and fell between the mounds of grain. We wanted to join the detachment. We moved quickly 100 or 150 meters between the piles. The field was still clear.

The Germans put a dense firewall on the left side (from the forest), the fire was also thickening somewhere in the front on the right. The fire from the machine gun was clearly visible. The Germans used every 4th or 5th tracer or light cartridge in the ammunition belts. It was getting lighter with each passing moment. After a few minutes – or so it seemed to me – it was completely light. The situation was getting hopeless. The Germans had such perfect conditions for observation and were so shot that every little movement in the field caused an avalanche of accurate fire.

The Germans, busy with the fire of the unit, noticed our rear guard only after a good moment. This allowed us to go beyond the lines of the last mounds of grain for several dozen meters. Crawling I came across the wounded 2nd Lt. “Dunina”, the commander of our platoon. He was injured in the stomach a moment ago. He was still completely conscious. He gave me his surname (I forgot it of course and “discovered” it again only after the war) and asked to notify his family. After a while he was speaking with obvious difficulty. I remember asking him

stupidest question that could be asked in such a situation: “do you hurt a lot?” He grimaced and with great effort said: “Starża is too late, I warned him. You won’t get through, try to go back, maybe you will. ” He tried to say something else, and suddenly fell silent. I no longer understood his last words whispered with the utmost effort.

I looked around: all around in front of me were lying, motionless insurgents, probably dead. A little farther on I saw a yellow suede windbreaker; this is what Zbyszek Przestępski had.

When I came to the area of the massacre after the war with Andrzej Krupiński’s father and Zbyszek Przestępski’s mother, it turned out that I was right. In the field that I am describing, there were many single graves and one collective one. Those who died were buried by local peasants in the place where they fell. In the mass grave, the wounded were taken alive and killed or shot. I managed to quite accurately determine the place to which I crawled on August 2, 1944, at dawn. I pointed to one of the nearest graves and said: more or less in this place I thought I saw Zbyszek’s airgun. The digging began – there was a suede windbreaker pierced by four bullets.

Andrzej’s father, while looking for his body, dug up a few other graves – we did not

find anyone from our section. It took a lot more time and people to search all of them. Mr. Krupiński stated that he would organize a team with which he would carry it out. Now he has to go back to work in Silesia. I came back with him. At that time, I was working in Opole Silesia. He did not notify me about his next trip to the Boerner field. I found out much later from Mrs. Przestępska that he had searched all the graves and had not found Andrzej. I cannot forgive him that I will no longer find out where she died and in which grave Hanka is buried.

The Germans must have seen that I looked up because two short series of machine guns flew by right next to me. I clung to the ground. The body of 2nd Lt. Dunin. I looked back – I couldn’t see any of my rear guard colleagues. I have no idea what happened to them. We crawled within a short distance of each other. I don’t think any of them have overtaken me. Nor is there any wounded or fallen person in sight. Had they withdrawn while I was talking to Second Lieutenant Dunin. It was so short that they couldn’t be far. I called in an undertone, then louder. There was no response. The Germans couldn’t hear much too far. But I was afraid to move, because they were very well shot and they were definitely still watching the field. The shooting almost stopped. Occasionally single rifle shots were heard, a short burst of machine guns rang out once or twice.

From the Boernerow side, I heard the whirr of a tank engine igniting. I knew that voice well. During the training, we had an apprenticeship in a locksmith plant located close to German military automotive repair shops. There were no tanks in them, but there were heavy artillery tractors that had identical engines. I had the opportunity to observe the traffic in the yard of the workshop, and I also remembered the characteristic voice of the engine being started and heated. I couldn’t be wrong, the tank was definitely launched.

After some time he left and rode in the field in weights. The commander sat in the open turret with a submachine gun in his hand and from time to time sent a short burst. He was definitely killing the wounded. At one point, somewhere near me – I thought that from one of the mounds of grain – a single rifle shot was fired. The tank stopped for a moment, the hatch on the turret slammed shut, and it drove on.

I don’t know who was shooting and whether he hit the German sitting in the tower. At the time of the shot

, I was looking the other way. But I know we went unarmed. We were ordered to leave all weapons in Warsaw (I forgot about my seven, of course). Two rifles were in our rear guard, but I didn’t see any of my colleagues for a long time. I know that the spearhead and the vanguard were also armed. Was someone from the rear guard shooting?

A moment later, an off-road car with four Germans left the Boernerowo – Wawrzyszew road. He was so close to me that I could make out the brand. It was – I remember exactly – Stoewer (i.e. Czech Tatra, produced under license in Szczecin). Again, a single rifle shot, somewhere not far from me, a few short bursts of a submachine gun from the side of the road and the car pulled back towards Boernerow. The middle of the road, paved with large “cobblestones”, was very narrow and convex; there was deep sand on both shoulders. The Germans were afraid to turn back, they preferred to go backwards.

I was expecting a tank or a few German cars to come here in a moment. To my surprise, it went completely quiet. Only the sound of a tank riding in the distance came from a distance, but that too soon fell silent. Somewhere nearby, I heard larks. I realized that they had been singing for a long time, only in nervous tension I had not noticed it yet. I don’t know how long I lay motionless, afraid to even turn my head. It was a beautiful hot day. I finally looked at my watch. I was surprised to find that it was only just around five o’clock. I’d be ready to swear it’s already afternoon.

I began to slowly and carefully retreat towards the nearest mounds of grain. I assumed I had to be perfectly visible. I was crawling literally on the ground and very slowly. When I finally got to the first kopecks, I was so tired that I thought I would never be able to move on.

I cannot say how long I rested. It seems to me a very long time, but today I know that in these kinds of situations you completely lose track of time. It could be several dozen seconds as well as several minutes. I remember that I was terribly thirsty. I did not have a canteen with me, which I filled with water in Żoliborz. I have no idea when or how I lost it. I remember throwing away the “captured” cigarettes because they prevented me from crawling. I had a canteen firmly strapped to my main belt. I don’t think I have unfastened it. Apparently she had to break away while crawling. Single droplets of water hung on the ears of corn after a heavy overnight rain. Lying under the mound, I drank whatever I could reach. It turns out that this way you cannot quench your thirst, but you can remove the terrible, paralyzing dry mouth.

There were no noises from the field and the Boernerowski grove. So I decided to crawl between the mounds towards the village of Wawrzyszew. The last of them were placed almost opposite the first houses of the village and 10, maybe 20 meters from the road. I did not know if there were any Germans in Wawrzyszewo, nor did I know if they were watching the road.

I took one sheaf from the nearest mound, picked it up so that it covered my PW sweatshirt, calmly (or so it seemed to me) walked the road and entered the nearest yard. There was no one in the yard, not even the dog barked. I threw the bundle on the ground and, jumping over the fences, I ran as hard as I could towards Żoliborz, as far away from Boernerów as possible.

One of the fences was taller than the others, or maybe I was too tired. I couldn’t jump over. I sat down on the ground underneath him. A middle-aged woman peeked out from a small brick house. She waved her hand at me. I got up with difficulty and, rather staggeringly, I reached the door and went inside. There was a jug of milk on the table,

and an open loaf of bread. Suddenly I felt terribly hungry. I heard: “There are no Germans in the village, please sit down and eat something”. I started to eat and after a while I fell asleep sitting up.

Last night I didn’t sleep a wink, and we didn’t sleep much the previous night. A tug on my sleeve woke me up. The hostess woke me up violently: run away, the Germans are walking around the village, I think they are looking for someone. She cut a thick chunk of bread, pushed it into a bag, literally pulled me out into the yard. I was still half asleep. Somewhere in the distance, I heard indistinct screams. I woke up immediately and marched through the hedges towards Bielany.

Bielany

When I was leaving Wawrzyszewo, the sun was already high. I think it was around noon. I arrived in Bielany in the early afternoon, dodging on the way due to the unfamiliarity with the area, and also trying to avoid meeting the Germans. How I managed it – I don’t know. I was really lucky.

The streets in Bielany were completely deserted, and there was no one in the windows of the houses. I knew that Hanka’s father lived on Bartycka Street. I did not know him so far and based on Hanka’s stories, I had a rather poor opinion of him. However, I decided that since I am already in Bielany and we do not know what will happen to me next, I should try to inform him that Hanka probably died this morning …

I still did not admit this thought, but if I die too, no one will ever know what happened to it. Before the Uprising, Hank, having learned that the battlefield of our unit would be Żoliborz, and maybe also Bielany, gave me her father’s address “just in case”. I remember him.

I had never been to Barcicka Street, but I knew its location from the city map. I got there without any problems, but with my soul on my shoulder, because this street is located near the CIWF, a fortified German resistance point, which was not captured yesterday.

I found Hanka’s father alone in the apartment. He was very scared. He greeted me kindly. He knew about my existence. He asked about Hanka. I replied that I was very afraid for her, but still hoped she managed to get out of the trap we fell into. The conversation was still completely off, I could see that he was scared by my presence and the pistol and two grenades that I took out of my pocket and sat down on the armchair. He could not give me any information about the situation in Bielany. After a few questions for which I didn’t get any meaningful answers, I left. I never met him again. I don’t know how I knew he survived the war. He did not seek contact with me, he did not try to find out where Hanka’s grave was.

I went out into the street but didn’t know where to go. You certainly had to distance yourself from the CIWF, but what next? From someone who looked out from behind a slightly ajar door, I found out that German patrols were hanging around the streets of Bielany in the morning and arrested people who turned up on them, but now there has been a relative peace for several hours. Apparently, there is also a unit of insurgents in Bielany, but he does not know anything specific about it.

I did not know if this was true and where to look for this unit. I was hoping it might be part of our company which, like me, managed to escape from Boernerow. It was necessary, however, to look further.

It was not easy, however, because the few who managed to answer either did not know anything or were afraid to speak. After all, I could also be a German provocateur. A lonely guy in a uniform and with a gun, loitering around the streets under the very nose of the Germans, could not inspire confidence.

However, while weaving between the houses, I managed to obtain some information from sneaking people. The news that there were insurgents in Bielany was confirmed. Someone told me the direction in which they were said to have been seen. This is how I got to Kleczewska Street, where the Boy’s team from platoon 237, my platoon, was in one of the villas (on the corner or the other from Kasprowicza Street) !!!

Kleczewska Street

I did not know any of the soldiers of this team. Some of them I remembered from the meeting point. They, on the other hand, remembered me well. I was probably the only one in the entire company in a PW jacket with insignia and a belt, and a forage cap with a pre-war eagle. It turned out that this team remained in Bielany, as the news about the battalion’s departure to the Forest did not reach it.

They took me well. Always one more, with a gun. The story of the march and the Boernerow massacre was received with great disbelief. They mocked me that some German sentry was shooting from time to time out of fear and it is not

known which of us was more afraid. I was fed, assigned some bed, on which I fell asleep immediately. Apparently I was sleeping very restlessly. It still seemed to me that Hanka was next to me and that I had to protect her from something.

After a night of sleep in a villa on Kleczewska Street, I woke up early in the morning, physically tired and in a terrible mood. I couldn’t figure out where I was and what I was doing here. While looking for a bathroom, I came across our hostess and I asked where Hanka is. She realized that I was asking about one of our liaison officers who were there with us, only the names (or pseudonyms) were wrong. She started explaining to me that yesterday she went to sleep in another friend’s house, because there are too many of us here. It was only at this point that I woke up and realized what happened yesterday.

On August 3, we learned about the return of the “Serb” battalion (later renamed “Żubr”), which included our company, to the Workers’ Capture area. Boy made contact with him and informed him of our forward outpost. Then he moved his unit out and, patrolling the Bielany area, he met with Serb units. He left me, one of his soldiers and two female liaison officers at the post at Kleczewska Street.

When the Germans attacked the troops from the Forest on the Workers’ Capture, Boy’s group took a position at their back, on the roof of the house on Hajoty Street. They surprised them and eliminated the service of two HMGs, obtained two (or maybe even three) submachine guns, rifles, pistols and ammunition. The attack of the Germans broke down, and as a result of the insurgents’ counterattack, they withdrew towards Piaski.

At that time, I was standing at the observation post in the attic of “our” villa. At one point, between the roofs, in the direction of Piaski, I saw a slowly moving column of trucks. It was far away, from 200 meters. Loaded the rifle with tracer ammo, took aim, and fired. The bullet passed right behind the car. The second time I gave more advance – the bullet went through the center of the sheet covering the chest. The car drove on. The third time I gave even more advance – the missile passed through the driver’s cabin, the car turned and stopped. Unfortunately, I only saw the end of his chest between the roofs.

I do not know if it was the end of the transport column or if the Germans decided that the journey was too dangerous. In any case, the traffic on the visible road (street?) Has stopped. After a good moment, he ran it so fast that I didn’t even have time to assemble myself to shoot, an off-road car and a motorcyclist after a while.

In the afternoon, Boy’s group returned complete, unscathed and unbroken, laden with the acquired weapons and ammunition. In the night of the 3rd to 4th battalion “Serb” retreated to the Forest again. And this time, Boy’s forward outpost was not notified of it, although communication with the battalion’s command worked perfectly. The distance between us was small, the liaison officers ran smoothly and relatively safely, because they were residents of Bielany and their presence in this area did not raise any suspicions. A patrol of the “Żniwiarz” battalion under the command of a cadet also remained in the area of the Workers’ Capture. “Azota” (Jan Suchowiak). We had communication with him. But in the event of the discovery of our facilities, we could not help ourselves, and given our modest strengths, the fate of both of our groups was doomed in this case. It was obvious that our commanders’ rules of conduct were of dubious quality not to deal with such trifles as notifying their own outposts that they remained in no man’s land, without communication, orders and support.

On the next day, the Germans, knowing about the presence of the insurgents, systematically searched all houses in our part of Bielany. They also searched “our” villa. We were sitting in a closet in her attic, the entrance to which was covered with a box of sand, and the floor of the attic was covered with a layer of sand, which, after passing us to the closet, the messengers leveled and scattered some small rubbish to create the impression that no one had been here for a long time . The sand on the floor and the sandbox in the attic complied with the fire regulations in force and strictly observed by the Germans. Fortunately, the Germans came without dogs and fell for it. I do not know exactly how it was with the “Azota” branch; I guess they just didn’t get to him.

After this miraculous rescue, we came to the conclusion that we were going to the forest at night. Further staying in Bielany – and without an order – does not make any sense, and it is better not to count on another miracle. Of course, “Azot” was informed about the decision to go to the Forest. We left around 23 o’clock. Boy was driving. In total, 10 to 12 people were walking along with the liaison officers. We also ran under the guard of a guy who was caught in our neighborhood and behaving suspiciously, who claimed to be Lieutenant “Orlicz”. There were many indications that he was a German spy. These suspicions were fully confirmed

and he was sentenced to death and shot in the Forest by the sentence of the field court.

We went to the forest without any hassle. We were only stopped by an outpost of forest troops. After explaining who we are, filing reports and handing over to the gendarmerie of the escort we were brought, we received information on where to look for our company.

Perhaps it is worth mentioning here what was the first action of the gendarmerie in order to find out whether Lieutenant “Orlicz” is really an officer. He was given a Polish rifle – without ammunition of course – and ordered to take out and unfold the lock. He couldn’t. Further investigation was already facilitated.

Around noon we met Sec. “Zycha” (Zdzisław Grunwald) from our company, and a little further in the village, lieutenant “Starża”.

Lieutenant Starża

in the Kampinos Forest

“Boy” reported to the commander of the 2nd company, Lt. Starży, the arrival of our unit and briefly reported the course of events in which he participated. Starża took it quite coolly and thanked him for reporting. Of course, there was no question of leaving the forward outpost at the mercy of fate twice. “Boy” in his report also informed “Starża” about accepting me to his team and explained where I came from. Starża did not consider it appropriate to ask me what was going on near Boernerow at the end of the column he was leading.

After Boy had left, I went over to Starża and asked if he could spare a moment for me. He agreed, and I realized that he didn’t recognize me. Ultimately, nothing strange about that. He did not have to remember me from the emergency meetings, and he talked to me for a while when we brought the weapons to Podleśna Street. I reminded him that I was walking in the rear guard and I am very concerned about my closest colleagues and my fiancée who walked in the last platoon of the main column. I asked who I could get any information from. At that time, I already knew that we had big losses near Boernerowo, but I did not know that they were so big.

“Starża”, who so far talked to me politely, but with the look of a dignitary who is told irrelevant stories by someone with no meaning, literally fell into a frenzy. He started shouting at me that I was repeating rumors, that I was spreading defeatism, that there must be losses in the war and that it was a pity for the few people who died, but thanks to his decision to go to the Forest many were saved. Besides, he and his team passed almost without losses. Those who died are to blame for themselves, because they have fallen behind instead of rushing forward. Some people are still missing. They haven’t come to him here yet. They probably wander somewhere between the forest divisions. And some of them came back, like me, to Żoliborz or other parts of the city, e.g. Powązki.

He only forgot to add that the Germans must have noticed our unit before entering the Boerner field and they let the front guard and the head of the column pass to prevent it from withdrawing. I asked him if he was interested in how 2nd Lt. “Dunin” platoon commander of his company, and what happened at Boernerow after he passed. The answer was a steak of vulgar insults and the threat of a court martial for spreading defeatism.

At this point, everything became clear to me. It was a desperate defense of the Starry with the method of all tricks. I decided to conduct my own investigation into the tragedy near Boernerow. Contrary to appearances, it was not easy during the Uprising. Later times were also not conducive to such activities. People were often afraid to speak, or in the face of the general campaign of the PRL authorities against the Home Army, they avoided statements that would testify to the ineptitude or criminal carelessness of some of its commanders. However, I did gather some facts. I list them in the order I recall them, without prioritizing or credibility.

The company commander (“Starża”) did not know how many people he led to the Forest. He did not try to find out, nor did he try to figure out how many people had died at Boernerow. These were taboo subjects, to which he returned only to deny that the losses were very great. I was not in captivity with him, but I know from my colleagues’ accounts that he avoided this subject.

In my opinion, there were 160 to 180 people walking. I can still see a long row of colleagues marching through the Workers’ Capture and Sands. It was just before dawn and they were clearly visible against the empty field. In Kampinos, I counted a little over 20. Certainly there were also those who got lost during the escape and joined other forest units. I know only one such case personally, I have not even heard of others, so I guess there weren’t many of them. I did not meet anyone, nor did I hear about anyone who would get out of Boernerów to Żoliborz or possibly, like me – to Bielany. I do not exclude that there could be such cases, but again they may concern individuals.

They fell at Boernerow

After many years, I took part in military exercises. We came back to our accommodation in the evening after a rather strenuous day. At one point I noticed that the area was similar to what I remembered from the transition to Kampinos. The soldiers were also going goosebumps. I stopped them and tried to explain that I would like to try to recreate the situation from years ago. Nothing came of it. They were tired and didn’t really listen to what I was saying.

In the evening, after supper, I gathered the company by the fire and told briefly the story of the march to the Forest. I also said that I was unable to recreate the image that I remembered and that my calculations of the losses incurred at that time were very different from the official data. After the soldiers had gone to their tents. One of the platoon commanders came to me and reported that tomorrow before dawn our entire company and part of the neighboring company – 180 peasants in total – were at my disposal. They all volunteered.

The next day it turned out that recreating the remembered situation is not so easy. The row of 180 people seemed too long to me, while 100 (this number was roughly due to Starża’s vague explanations) was definitely too short. The soldiers, without the slightest sign of discouragement, patiently endured the arrangement of columns of various lengths and shapes. I thanked them warmly for that later.

I don’t know how many of my comrades-in-arms were really killed at Boernerow. I only know that my relatives and friends died there and that they died because of stupidity, lack of imagination, or perhaps the fanfare of “Starży”. They died only after a few hours of the Uprising. Their participation was so short that even their colleagues from the same grouping, from the same platoons, do not remember them. Platoon 237, which went last, suffered the greatest losses. So big that when I was interrogated by the secret police in 1946, they said that I was trying to mislead them, because there was no platoon with this number.

On the night of August 1st, three companies were transferred to the Forest. Two passed without any obstacles or losses. Ours – with huge losses. The other companies were led by guides. “Starża” refused to take the guide, claiming that he knew the way.

The entire battalion moved back to Żolibórz and the Workers’ Capture without any major obstacles and returned to Kampinos on the next day, when the German ring around Warsaw was already tightened.

“Boy” moved with his squad at night from 4th to 5th. True, this unit was small and it was easier for him to slip through. But we also passed the day (or rather the night) later.

Finally; on the night of the 15th to the 16th, that is, after more than two weeks of the Uprising, a unit of about 800 people moved from the Forest to Żoliborz, heavily loaded with drop weapons and ammunition. We passed (I was in this squad) without a single shot.

So it was possible to safely pass through the first night of the Uprising. And here is the most serious accusation. The Home Army intelligence had informed for several days before the Uprising that part of the SS Herman Goering armored division, withdrawn from the eastern front, and a unit of Ukrainians were stationed in Boernerów and the adjacent forest. We were walking through the bare field, unarmed, most of us without any combat mortar, about 150, maybe 200 meters in front of their outposts, and that when it was just starting to dawn.

The intelligence reports even reached me. Before the first alarm, Jurek Miller warned me not to go to Boernerów (we had our hiding place there, where we left some lumber that was useful for exercises) because there is a German armored unit there and the hiding place is temporarily closed. If the rank-and-file and section commander knew about it, could the company commander not have known? A question arises whether the route of the march was agreed with the battalion commander, Captain “Serb”.

Along with our company, several civilians also moved to Kampinos. I did not see it personally, but all who survived the transition to Kampinos agreed it. One of the civilians was distinguished by the fact that during the whole time of the fire from the Boernerowski forest, he did not hide himself, he marched with an even step, leaning on an elegant cane. The Germans aimed at him with several machine guns. No bullet grazed him. It was said that it was supposedly someone from the civilian authorities of the Polish Underground State.

Here is a quotation from the book of Lieutenant “Zych” “Żubry na Żoliborzu” (page 83): “In very harsh words he attacked (talking about the aforementioned civilian with a cane and his meeting with Starża in Kampinos – MB note) cf.” Starżę ”that he had lost the unit he led, he was threatening to take the case to a court martial. The dispute was very acute, it is good that both of them were not armed, because the choking could lead to disaster ”.

The above-mentioned book contains a list of the fallen soldiers of the “Żubr” battalion. It includes 244 soldiers, liaison officers and nurses. It is definitely not full. It includes everyone whose surnames, nicknames, or only military rank could be established, and the fact of death on the battlefield or in the hospital was beyond doubt. On this list of 71 dead, the place of death is given – “near Boernerow”. Assuming Starża’s statement that about 100 people were in his unit, it means that the losses amounted to over 70%, not in combat or as a result of an extremely cunning ambush, but during a routine march through the well-known area. Detailed data in the aforementioned book shows that those who died at Boernerowo constitute over 29% of the total fallen of the “Żubr” battalion (three companies, staff, communications, nurses, intelligence, etc.) throughout the Uprising. More than half (55.5%) of all the fallen 2nd company (Starża) during the entire Uprising died near Boernerowo.

During the Uprising I had contact with “Stara” only twice. He definitely avoided me and knew what I thought of him.

Gdańsk Railway Station

Our company did not take part in the second attack on the Gdańsk Railway Station (from the Żoliborz side on the night of August 20-21). Although in the aforementioned book “Żubry na Żoliborzu” there is a mention of a platoon led by Lieutenant “Gedroyc” (new platoon commander 237), with a reinforced Piat pitcher, but in my opinion this information is inaccurate. This unsuccessful and uncoordinated attack, due to the lack of good communication with the troops from the Old Town, brought, just like the first, a few days earlier, very large losses in the number of dead and wounded.

In the aforementioned book, only one killed (“Bończa” from the Piata service) and not a single wounded from platoon 237 is mentioned. With the enormous intensity of fire from the side of the railway station, the Chemical Institute and from the viaduct over the tracks and the necessity to walk across the empty field to the German stations located under the wagons on the tracks of the station, it is impossible for any platoon to be scratched.

After returning from Kampinos, our company took up positions in the fire brigade building on the corner of Słowackiego and Potocka Streets. Late in the evening of August 20, I was handed over to me (unfortunately I don’t remember who) Lt. Starża’s orders to report to Piat (an English anti-tank grenade launcher I had brought from Kampinos), four missiles for him and two ammunition for the command of the units that had attack the Gdańsk Railway Station at night. One of the ammunition was the shooter “Bończa”, which I had known for over a week. The second was assigned to me a day or two earlier. All I remember is that he was slim and tall, and his nickname, I believe, had something to do with a bird; it was another “Orzel”, “Vulture” or “Falcon”. I will call him “The Bird” here, although that was certainly not his nickname.

We reached the command in the area of Generała Zajączka Street maybe half an hour before the attack. I remember being completely surprised by our appearance. Of course, they were happy to receive the support, but all orders have already been given. After a short deliberation, we were directed to the attacking unit on the left wing. If a platoon from our company took part in the action, in addition “my” platoon “237”, undoubtedly Piat would strengthen him, and not a unit, completely unknown to us.

On the line everything was ready to attack. Our appearance was a complete surprise. We were directed to the edge of the left wing, which was supposed to attack the tracks near the viaduct. To my question, what are the goals ahead of us requiring the use of Piata (bunkers, fortified positions), I did not receive any specific answer. I didn’t even get a sketch describing the situation on our episode. I also did not know the identification signals of the troops attacking the station from the Old Town side. If both of our attacks were successful, we could fire at each other.

During the attack, I was on the edge of the left wing, just under the embankment of the viaduct. There was no one left to my left. If we had successfully reached the tracks – and we weren’t already missing much – we would be the first line on the left flank. Apart from the Piata with four loads, I had a Smith Wesson drop-down revolver, and my ammunition had some pistols. Power! against the fortified positions and German bunkers.

We managed to get to about half of the field in front of the tracks without any problems. The Germans did not expect that someone could attack right next to the embankment, where the terrain rose slightly towards the viaduct and created excellent conditions for attacking attackers.

I saw a machine gun nest in front of me under a freight car standing on the train tracks. I ordered Bończy, who was closest to me, to give me one Piata bullet. Loaded up, took aim, fired and nothing. Dud. I did not check if the “Bończa” was fitted with a fuse! We practiced this so many times that it never occurred to me to forget it.

The armament of the missile required unscrewing the metal cover on its protruding tip, removing the container with the fuse, unscrewing it, removing the fuse, inserting it into the missile and screwing the cover on. Simple and easy, but not under fire and bearing in mind that the instruction manual warns that the fuse is very sensitive and detonates on a light impact.

I threw “Bończy” a bunch, probably the worst in my life, ordered a second bullet, but with a fuse. He passed, I shot the same spot. I had to hit the axle of the wagon or its suspension, because the wagon tilted towards us and the machine gun stopped.

I saw flashes of shots by another machine gun a little further to the right. I shouted to the other ammunition for a projectile (“Boncz” was gone). He handed it to Bończy and he handed it to me. Shit, no fuse again. I’m calling for the fuse. He tosses the container at me, I can’t find it for a moment. Finally I find and at the same time I hear the scream of “Bonczy” they hurt me, I am wounded. I load Piata, hear whistles and missiles hitting the ground, right next to me. The bastards fired. I aim and shoot. You can no longer see the machine gun flash from the blast site.

Instead, hurricane fire in our direction begins. Apparently the flash of the Piata shot betrayed our position. The situation is bleak. On the line you hear commands and calls to withdraw. The attack failed. He tells “Bird” to pull “Boncza” towards our starting position, and I struggle with the heavy Piat, still catching on uneven terrain – with the base, then with the butt, then with the metal shell of the projectile.

At one point, as I brush my hair back from my forehead, I feel as if I have blood on my right hand. Shit, I don’t know when I got hurt. But apart from a slight pain in my hand, nothing is wrong with me. The hand is functional, it only bleeds a lot. While crawling out of the primitive holster, a revolver fell out of me for the second time. Fortunately, he was on a string made of parachute lines from the Kampinos airdrops. I draw him to me and console myself that revolvers are much more resistant to dirt than pistols. Then the cause of the bleeding hand is explained. There is a deep transverse groove on the metal ferrule of the revolver handle, a trace of a hit by a bullet, probably a rifle. Correcting the revolver that was constantly coming out of the holster when I crawled, I had to cut myself on the sharp edges of this furrow. I look around. I can see someone 10 meters away crawling rapidly towards our lines. I think it’s “Bird”. I call out to him, something suits me, but I can’t understand it.

I hear a groan, somewhere to the right of “Bonnie”. I leave Piata and crawl towards him. I try to move him, I can’t, he screams in pain. I drag it a meter or two at a time, closer to our positions. A little further to the right, I see a nurse dragging another wounded man on the cloth. He’s calling out to me. Turns out she thought I was hurt too. I am asking what to do with the wounded “Bończa”. I can’t cope with him. He advises me to wait for the sanitary patrol. Despite the strong fire, the nurses kept dragging the wounded from the field.

I leave “Bończa” and come back for Piata to bring him closer. I can’t find it, even though it’s not a match. Had someone taken it already. After all, there was no one in our immediate vicinity. So I am trying to return to Bończa. The Germans fired a machine gun fired somewhere far to the right, just above the ground, almost parallel to the tracks, but closer to our lines. The tracers are clearly visible. There is no way to pass. I feel that I am starting to lose my strength; could I be weak due to the loss of blood. I don’t think I’m bleeding that badly; the cut on my hand seemed completely superficial to me.

Finally the nerves let go completely. I do not care. I lie down on my back and need to rest for a while. I don’t know how long I was so numb. I think only for a moment, because when I woke up, the situation was practically unchanged. The HKM fire blocked my way to my own lines. I am looking for “Bończa”; i can’t see him I am calling in a low voice – no answer. I rise on my elbow to see a little better and immediately fire from several directions. I cling to the ground.

I conclude that the only way out of this killing field is to move along the firewall towards the viaduct embankment. At the viaduct itself I find a small depression which I will crawl out to Generała Zajączka Street. Now just run across the street and, between the houses behind it, get to their rear. A nurse crawls over to me, dragging an unconscious wounded man; she is extremely exhausted and asks me for help. It encourages me to make one more effort. We drag the wounded. We are finally relatively safe. Soldiers and nurses run up to us. Unfortunately, the wounded man, transported with such effort, is no longer alive. Someone asks me if I know anything about the wounded in the foreground. I report about “Bończa” and the rest of Piata, and that I do not know if “Ptak” managed to withdraw; I saw him alive close to our lines.

I am completely exhausted and I am very thirsty. Someone gives me a flask of water. I cannot hold it and it falls out of my hand. Suddenly there is “The Bird” among the people around me. I hear his story of how the second ammunition was killed and I was injured and how he helped me get out of the fire. I do not have the strength to straighten this nonsense, I have a bloody discharge uniform jacket, my right hand is covered in blood. Some nurse and “Bird” lead me to the dressing point. I explain that it’s just a cut. They don’t want to listen. I get hot tea (?) And bandage my hand. It is only confirmed to be a deep cut. They examine the hilt of my revolver and try to determine under what conditions it was hit by a bullet. They conclude that the revolver probably saved me from being shot in the stomach. After a short rest, I leave the dressing point with “Bird”. A girl leads us through interconnected cellars and ditches. We go out into the fresh air, we hear single shots and short bursts from the side of the station.

“Ptak” begins long reflections on the course of the attack on the station. If he was as well prepared as our participation, then… and here a very long and varied bunch of opinions about our commanders came to my head, which amazed me. I have not heard such a repertoire of sophisticated curses in a long time. Finally, he stated that his family (or friends) lived not far from here and had to drop by them. He is so upset that he needs a drink; there will always be some alcohol for them. He wanted to take me with him. I declined. Maybe a little alcohol in this situation would do me good, but I did not have the strength to talk and discuss with strangers. I heard: “then come back alone, just don’t throw me out. Tell me they still detained me to help at the sanitation facility. I’ll be back in an hour. Bye then”. He never came back. I don’t know what happened to him.

After returning to the Fire Department, I reported to “Starży”. He greeted me with the words: “Again, only you managed to get out of it alive; You wrapped your handle, that kind of wounded, what? ” I already knew about the “sympathy” he had for me and I was in a mood where it didn’t matter anymore. I answered him – I remember every word – very slowly and clearly: “The Bird also came out of it, they stopped him to help carry the wounded at the sanitary station. He should be back soon. I am not hurt. It’s just a cut… ”. At this point, I started taking my revolver out of its holster to show it to him, and at the same time

finished the sentence “cut on my shot revolver; I was lucky, as during the passage under your command at Boernerowo and in Bielany, when you did not bring the “Boya” outpost to go to Kampinos “.

I thought he was going to be damned for this. He reddened and jumped up as if he wanted to pounce on me. But at that moment, I finally managed to pull my Smith Wesson out of its holster with a bandaged hand. “Starża” stopped abruptly, broke off the bundle in mid-word. I held the revolver by the hilt for a moment and looked at the terror in his eyes. I think he thought I was about to shoot.

After a good moment I turned the revolver and, holding the barrel, I handed it to him saying “not loaded, I cleaned it of sand and earth and did not load it”; I interrupted my voice for a moment and added “but I still have my private seven, charged.” It was not true. I gave the seven to one of my colleagues in Kampinos after receiving the Smith Wesson drop. “Starża” did not take my revolver, cursed ugly, turned and walked away. It was my penultimate contact with him.

Injury

During the withdrawal of our units from the Olejarnia [1]) in Marymont on September 14, I was injured. In the connection ditch, close to the Fire Department, a missile, probably a mortar, exploded a few meters away, fortunately, behind the bend of the connection ditch. It saved me from shrapnel, but I was stunned and passed out. My friends pulled me out and moved me to the Guard building. There I was revived quite quickly. However, it turned out that I am completely deaf, cannot speak and have trouble staying upright. They did not send me to the hospital because there was no room for even the seriously injured, and I was only injured. The company doctor allowed me to be left in the ward and recommended that I be released for two or three days from the service. My deafness passed after a few hours, only a strong tinnitus remained. I was still having trouble keeping my balance, and as my voice returned, I began to stutter terribly.

The next morning I was sent to “rest” at the battalion command. I was sitting in the basement in the “hall” as an informant, I was also supposed to report the incoming people. I was not very suitable for this, because I was still stuttering terribly and all information and reports lasted a very long time. To tell you the truth, I didn’t have much work to do there, because most of the people who came in probably came in without reporting and no one complained about it. So I sat on a stool and slept, and my arrears were enormous.

At lunchtime, one of the non-commissioned officers relieved me. When I returned, I found out that there was a briefing in my absence, and now a few officers are still there and they are discussing something, but probably not for business purposes. In a moment, one of them came out and did not close the door behind him.

I heard lively voices, there was no doubt it was drunk. From the voice I recognized only one – “Starża”. The discussion alternately became louder and louder. I couldn’t quite figure out what it was about. I began to doze. I was awakened by a loud exchange of views. At first I thought they were arguing. But no, it’s just the influence of alcohol. The subject was to consider whether, after the end of the war, the post of the starost was appropriate for a lieutenant and company commander in the Uprising, or too modest. “Starża” was the loudest and decisive saying that it was definitely not enough.

It seemed to me that in the fifth year of the war and the seventh week of the Uprising, nothing could surprise me anymore. However, I was horrified to hear this discussion and the level of the debaters. After some time the debaters left. “Starża” did not pay attention to the person on duty sitting in the corner. In the evening I asked to be moved back to the line. The next day, I was already in the Fire Department building.

Starża was awarded the Cross of Valor three times for his participation in the Uprising. I have not heard, however, that in the case of the Boernerow massacre and the two-time pointless exposition of Boy I Azot’s outposts in Bielany to almost certain destruction, by failing to collect it or even informing that the entire company is leaving for Kampinos, any investigation was conducted.

After being liberated from captivity and the end of the war, he left for Australia (USA?). He was the only one of our commanders who did not keep in touch with his colleagues and insurgent subordinates. Someone said he had some news from his relatives.

I admit that there is probably no other human being so hated by me as he is. Although more than 50 years have passed, I cannot forgive him the completely unnecessary death of Hanka and my best friends and so many colleagues, as well as the vile, cowardly defense against the accusation that they died because of his stupidity and fanfaronada.

Injured

I remember the last two weeks of the Uprising in a blur. The first few days after returning to the platoon, I was still in poor physical condition due to an injury. However, I was back to normal. The dizziness stopped, but I still stuttered severely. After that, we were almost constantly in action. The Germans were determined to liquidate the Uprising in Żoliborz. The worst part was the lack of sleep. I was walking, shooting like a machine gun, not really knowing what was going on around. I thought about only one thing to finally get a good night’s sleep. The next commander of the platoon 237, Second Lieutenant “Oksza” (Jerzy Staszewski), on September 29, in the early afternoon hours, sent me to the other side of Słowackiego Street with a report. I don’t remember to whom or the exact address. It was somewhere near the church of St. Stanislaus.

I went through it without difficulty, I just wandered a little in the backyards. I delivered the report. I was told to wait while my answer was ready. I don’t know how long it took, because as soon as I sat down I fell asleep immediately. However, I think not more than half an hour. When leaving, I was warned about the recent shelling of a nearby yard. I did not pay attention to it. After all, I was just walking and there was no direct fire, and artillery or air bombardment is a force majeure and nothing can be done about it. I was going back the same way that I came. In one of the courtyards I was, unexpectedly, fired at by a submachine gun. I fell to the ground. Fortunately, I was sheltered by some stalks, the remnants of a vegetable garden.

I was fired from the left side, but I couldn’t figure out where from. On the right was a fence wall, front and back, about the same distance apart, blocks. I had just left the basement of the one in the back, and I was about to enter the basement of the second one. I tried to crawl, but my every move caused the stalks to move and an instant burst from the automaton.

I had a revolver with me and a lot of ammunition for it, and two offensive grenades (Filipino). I couldn’t shoot because I couldn’t see the target. So I took out the grenade, unlocked it, nodded my stalks a little, and as soon as the burst ceased, I threw the grenade with all my might in the direction from which it was fired. Immediately, before it exploded, I jumped up and ran as fast as I could and fell to the ground a moment after the explosion. I did it, but I still had about 10 meters to run.

After a good moment, I repeated the previous maneuver. I was surprised that my grenade exploded very close, yet I was throwing it like the previous one, with all my might. I ran to the opening in the wall of the block of flats and jumped into the basement. There were some very scared civilians there. One of them pointed out to me that you are wounded; blood is dripping from the sleeve. At that moment, I realized that I had felt a strong blow to my shoulder while throwing a grenade. I haven’t thought about it. Now I understood why the grenade flew so close.

Some old woman took care of me. She helped me take off my jacket, rolled up her sleeve and said, “Clear shot. You can move your hand, that is, the bone is intact; you will be fine. Do you have a personal dressing? ” I have a dump. “Please give it to me.” She developed it and expertly put it on.

At this point, my nerves let go. I felt terribly tired, my arm started to ache, my forearm and hand went numb. I only dreamed of one thing to go to bed. But I had the answer with me. upon the report I brought, I had to bring it back. I felt that if I didn’t leave right now, then no force would move me anymore.